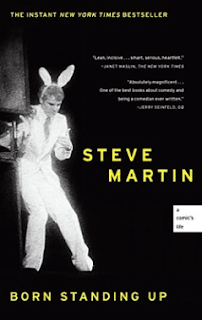

Actors and writers know all too well the truth of these lines. This is therefore a tribute to Steve Martin who wrote Born Standing Up, about a person he used to be.

"At age eighteen, I had no gifts," he disclosed in this engaging book. "Thankfully, perseverance is a great substitute for talent."

His high school jobs at Knott's Berry Farm and Disneyland had introduced him to the world of magic and comedy. Under the influence of a girl friend he gravitated towards studying - taking courses in - philosophy which gave him material for his early comedy routines. He is also a member of mensa but so far does not appear to have worked that into any comic work that I am aware of.

"I've decided my act is going ... avant-garde," he announced early in his career and elaborates in the book, "I am not sure what I meant, but I wanted to use the lingo, and it was seductive to make these pronouncements. Through the years, I have learned there is no harm charging oneself up with delusions between moments of valid inspiration."

He found in San Francisco "the cultural melange and the growing culture of drugs," that made the crowded streets of North Beach "simmer with toxic vitality." His years as stand-up comic made him aware of the loneliness of that calling. Unlike the teams that worked on shows like the Smothers Brothers, for which SM wrote until the show was cancelled due to political pressure, there was no team or band that congregated around a funny man. No "others" with whom to commiserate on a disastrous outing or to review a problematic performance or to plan a road trip.

SM likened the first time he did the Tonight Show to an "alien abduction: I remember very little of it, though I am convinced it occurred."

As this and all the above shows, the man is witty. But even he does not succeed in writing any scene of gut-heaving hilarity. Two scenes of what happened at the end of his stand-up routines when his audience declined to leave despite his best efforts and when he left by "swimming" over their heads, passed from out-stretched arms to others, come close in concept. I have to confess that visualizing them did not stimulate more than a chuckle, no more than the one-liners that fill this book.

He explored the psychology of comedy early on and concluded that the build-up of tension by a comic was often followed by an "artificial" release (punch-line). What, he wondered, if there is not any release /punchline? "What if I headed for a climax but all I delivered was anti-climax?" In many ways that was the essence of the SM brand. But it is not any easier to visualize or (I imagine) to perform. Certainly, to describe it would invite disaster.

His choice of the many comedians to which to pay tribute is interesting: Laurel and Hardy, the Smothers Brothers, the cast of Laugh-In, the team at Saturday Night Live, Don Rickles, etc. One wonders about the absence of Bob Hope, perhaps less so at the non-mention of Jerry Lewis. Pride of place was given to Johnny Carson who "enjoyed the delights of split-second timing, of watching a comedian squirm and rescue himself... He knew the difference between the pompous ass and the nervous actress and who should receive appropriate consideration... he served his audience with his curiosity and tolerance. He gave his guest--like the ideal America would--the benefit of the doubt: you're nuts, but you are welcome here."