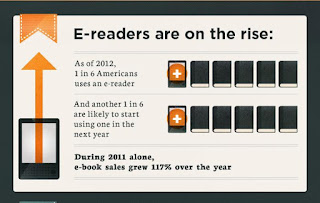

The website TEACHINGDEGREE.ORG (attribution link), from which the graphics of this blog have been obtained, is clear about this. There are more and more e-readers out there:

The shopping frenzy of the last few weeks--perhaps it continues--must surely have driven that point home. But there is good news; this does not spell the end of real books.

As it turns out, those who own an e-reader are likely to read more, even of books in print form.

For those who care that we do not slouch our way into illiteracy, this is a good thing. In addition there some circumstances, if one thinks about it, in which one form of books work better than others:

Reading with a child, for example, is best done with a book in print, while the great convenience of having many books in a small thin device makes travelling with a whole library best done with an e-Reader. (In any case, illustrated children's books test the current limits of e-publication.)

However one looks at it, this holiday season--here's to Books!

Saturday, December 22, 2012

Friday, November 30, 2012

The Elegance of the Hedgehog, a Review

November 30, 2012

"You ought to read The German Ideology" says Madame Michel, one of the two voices in this rich, beguiling novel, thereby almost giving herself away. For she has chosen to remain disguised as what she thinks of herself--or as what she thinks the world takes her for, a 54 year old concierge dressed in a "white nuptial meringue [undergarment] buried beneath a lugubrious black pinafore," who only "gets through her everyday life thanks to her ignorance of any alternatives." We are therefore treated to her spasms of fear, palpitations of being outed as the intellectual that she is (despite the fact that she only went to school from five to twelve); she is overwhelmed by the huge chasm of class/social distinction between the concierge and the occupants/owners of the apartments in this venerable building.

The other voice belongs to Paloma, a hyper-intelligent 12 year old who lives in fear of showing her freakish intelligence--that's how her classmates and family would treat it, or so she fears. She therefore hides it by reading everything her friend (who is second in the class) and carefully imitating the latter's work: French as "words in coherent strings, correctly spelled"; Math as the "mechanical reproduction of operations devoid of meaning"; history as "a list of events joined by logical connections"--all to "dumb down" the appearance of her true intelligence.

Each of the two voices take turns, more or less, to beguile us with considerations beyond the ordinary, of the sort if not common or familiar, one would hope is at least recognizable to those belonging to that which baccalaureate exercises frequently describe as the "community of educated men and women." Paloma's revelations are revealed as journal entries (in a sans serif font) while Madame Michel's (Renee) are only sometimes referred to as journal entries. One such memorable occasion is when she compares her journal writing to the hypnotic, unconscious rhythm of mowing grass: "The lines become their own demiurges and, like some witless yet miraculous participant, I witness the birth on paper of sentences that have eluded my will."

Both voices therefore hide their light under the proverbial bushel; they are wabi, Japanese for an understated form of beauty, of "refinement masked by rusticity." They each recognize in the other the radiance of intelligence. Paloma, while speaking of the concierge in her journal, cries out: "I implore fate to give me the chance to see beyond myself and truly meet someone." The novel shows how they each eventually make their own way towards the light.

Along the way, guarded and repressed as they are, they reveal flashes of gnomic insight. Paloma speaks of grammar as "an end not simply a means ... pity the poor in spirit who know neither the enchantment nor the beauty of language." Madame Michel makes breathtakingly short work of Husserl's Cartesian Meditations: Introduction to Phenomenology--a "ridiculous little book...[born of] hard-core autism." Chancing on Paloma's older sister's thesis on William of Ockham's Potentia Dei Absoluta, she concludes that academia has not always chosen wisely or well between "elevating thought" and "the self-reproduction of a sterile elite." Stunned by a still life by Pieter Claesz, even though it is only a copy, she declares she would without hesitation "trade the entire Italian Quattrocento [Fra Angelico? Donatello? Leonardo?]" for Dutch still life.

Not to make this review overlong, let it be said that there are passages of great tenderness and humor, as well as more gentle disquisitions on philosophical issues of moment. Madame Michel has found the library and it allowed her to expand her horizons; the VCR and the DVD have transported her senses. She is friends with pre-1910 Russian literature, movies from Yasujiro Ozu's cinematic equivalents of Pieter Claesz to the Blade Runner and the Terminator, music from Mozart (whose "Confutatis" appears at a most startling point) to Eminem; she reflects on the difference between doors that swing open and those that slide.

You ought to read this book!

"You ought to read The German Ideology" says Madame Michel, one of the two voices in this rich, beguiling novel, thereby almost giving herself away. For she has chosen to remain disguised as what she thinks of herself--or as what she thinks the world takes her for, a 54 year old concierge dressed in a "white nuptial meringue [undergarment] buried beneath a lugubrious black pinafore," who only "gets through her everyday life thanks to her ignorance of any alternatives." We are therefore treated to her spasms of fear, palpitations of being outed as the intellectual that she is (despite the fact that she only went to school from five to twelve); she is overwhelmed by the huge chasm of class/social distinction between the concierge and the occupants/owners of the apartments in this venerable building.

The other voice belongs to Paloma, a hyper-intelligent 12 year old who lives in fear of showing her freakish intelligence--that's how her classmates and family would treat it, or so she fears. She therefore hides it by reading everything her friend (who is second in the class) and carefully imitating the latter's work: French as "words in coherent strings, correctly spelled"; Math as the "mechanical reproduction of operations devoid of meaning"; history as "a list of events joined by logical connections"--all to "dumb down" the appearance of her true intelligence.

Each of the two voices take turns, more or less, to beguile us with considerations beyond the ordinary, of the sort if not common or familiar, one would hope is at least recognizable to those belonging to that which baccalaureate exercises frequently describe as the "community of educated men and women." Paloma's revelations are revealed as journal entries (in a sans serif font) while Madame Michel's (Renee) are only sometimes referred to as journal entries. One such memorable occasion is when she compares her journal writing to the hypnotic, unconscious rhythm of mowing grass: "The lines become their own demiurges and, like some witless yet miraculous participant, I witness the birth on paper of sentences that have eluded my will."

Both voices therefore hide their light under the proverbial bushel; they are wabi, Japanese for an understated form of beauty, of "refinement masked by rusticity." They each recognize in the other the radiance of intelligence. Paloma, while speaking of the concierge in her journal, cries out: "I implore fate to give me the chance to see beyond myself and truly meet someone." The novel shows how they each eventually make their own way towards the light.

Along the way, guarded and repressed as they are, they reveal flashes of gnomic insight. Paloma speaks of grammar as "an end not simply a means ... pity the poor in spirit who know neither the enchantment nor the beauty of language." Madame Michel makes breathtakingly short work of Husserl's Cartesian Meditations: Introduction to Phenomenology--a "ridiculous little book...[born of] hard-core autism." Chancing on Paloma's older sister's thesis on William of Ockham's Potentia Dei Absoluta, she concludes that academia has not always chosen wisely or well between "elevating thought" and "the self-reproduction of a sterile elite." Stunned by a still life by Pieter Claesz, even though it is only a copy, she declares she would without hesitation "trade the entire Italian Quattrocento [Fra Angelico? Donatello? Leonardo?]" for Dutch still life.

Not to make this review overlong, let it be said that there are passages of great tenderness and humor, as well as more gentle disquisitions on philosophical issues of moment. Madame Michel has found the library and it allowed her to expand her horizons; the VCR and the DVD have transported her senses. She is friends with pre-1910 Russian literature, movies from Yasujiro Ozu's cinematic equivalents of Pieter Claesz to the Blade Runner and the Terminator, music from Mozart (whose "Confutatis" appears at a most startling point) to Eminem; she reflects on the difference between doors that swing open and those that slide.

You ought to read this book!

Friday, November 2, 2012

NANOWRIMO

I received an email yesterday reminding me that November is the month during which those who sign up are challenged to write 50,000 words. See NANOWRIMO website.

This is no mean task: it works out to writing 2,500 words a day for twenty days, =50,000 words assuming one works on the basis of a normal five day work week. The website provides writers working on their individual novels with a sense of community that most writers do not have and might miss. I thought of signing up as a challenge to finish a spy novel on which I have been working for some months, tentatively titled Operation Kashgar. I have posted some of it on this site and more on a website for writers, AUTHONOMY.

But there are two other writing projects that clamor for attention right now. Together they might add up to 50,000 words, but they are not novels or short novels, they are plays. Every writer knows that if you write you must listen to the little voice inside. The plays will be a re-writing of Heaven is High and the Emperor is Far Away, A Play; for this I have had the benefit of a dramatized reading with comments submitted by the audience as well as readings I myself did before smaller audiences. The other is a dramatization that I have in mind of the investigations of Judge Dee. He was a real life figure from the Tang dynasty during which he rose from a county magistrate to the position of something like the Chief Justice of Metropolitan Chang-an (or Xi-an, both names for the Tang capital). His investigations have been "written up" by a gifted Dutch diplomat, Robert van Gulik, who died in 1967, see website.

Judge Dee's cases have a devoted following much as Rumpole or Hercule Poirot do, although the medium is different. Hence, reluctantly, I will not register with NANOWRIMO, but I welcome the challenge and hope to have written or re-written 50,000 words by the end of this month.

This is no mean task: it works out to writing 2,500 words a day for twenty days, =50,000 words assuming one works on the basis of a normal five day work week. The website provides writers working on their individual novels with a sense of community that most writers do not have and might miss. I thought of signing up as a challenge to finish a spy novel on which I have been working for some months, tentatively titled Operation Kashgar. I have posted some of it on this site and more on a website for writers, AUTHONOMY.

But there are two other writing projects that clamor for attention right now. Together they might add up to 50,000 words, but they are not novels or short novels, they are plays. Every writer knows that if you write you must listen to the little voice inside. The plays will be a re-writing of Heaven is High and the Emperor is Far Away, A Play; for this I have had the benefit of a dramatized reading with comments submitted by the audience as well as readings I myself did before smaller audiences. The other is a dramatization that I have in mind of the investigations of Judge Dee. He was a real life figure from the Tang dynasty during which he rose from a county magistrate to the position of something like the Chief Justice of Metropolitan Chang-an (or Xi-an, both names for the Tang capital). His investigations have been "written up" by a gifted Dutch diplomat, Robert van Gulik, who died in 1967, see website.

Judge Dee's cases have a devoted following much as Rumpole or Hercule Poirot do, although the medium is different. Hence, reluctantly, I will not register with NANOWRIMO, but I welcome the challenge and hope to have written or re-written 50,000 words by the end of this month.

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

A new Review in Amazon

This review is from: The Battle of Chibi (Red Cliffs): selected and translated from The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Kindle Edition)

Tjoa does an excellent job at meeting his goal of providing the original in a more "readable and lively language as well as internal consistency." It's a worthwhile though not an easy read. As a boy in the book says, "I cannot remember all the names."

At the outset, the author provides useful background. The historical events were originally recounted in a classic Ming novel, "Romance of the Three Kingdoms," written in 1400 by Luo Guanzhong. In turn the "Romance" was a compilation of work by writers living in the third and fourth centuries AD. (The Arthurian legend immediately comes to mind.) Luo's version is in four volumes of 120 scenes/chapters, the first 80 of which is about the decline of the Han Dynasty and the rise of three kingdoms, a period of transition from 184 to 280 AD. Tjoa characterizes the divergence as one "between imperial unity and fragmentation."

The selections chosen from the "Romance" center on the Battle of Chibi (Red Cliffs), dated 208AD, which Tjoa points out was "the tipping point" between the Han and Three Kingdoms periods. One of the three realms, the Shu, was led by Han loyalist Liu Bei. A second, the Wei, was led by Cao Cao the Usurper. Cao's plan was to become the new unifier of China, but his ambitions disqualified him in the eyes of the other two leaders. A third realm, the Wu led by Sun Quan, lay on the fringe of what was called All under Heaven, a name, says Tjoa, that equates to a Greco-Roman term, "the whole known civiilized world." An interesting pattern emerges in the novel's three-part structure. To my eye, a dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis unifies the diversity of the structural components as well as underlining the clash of cultures. The dynasty's decline is vividly characterized by its eunuchs, warlords, and rebels.

I became engaged in the story also through the spare, dramatically staged dialogue and the pleasing literary elements. The title of Chapter 8 ("Like Fish Seeking Water") is one example of how metaphor and poetry are used to illustrate what is going on. Here's another: "Screens, decorated with feathers,/Divide the space inside/Bamboo fences and fragrant flowers/Define the space outside."

A new world order emerges from the divisiveness, and though the country is no longer unified, neither is it so insularly focused. At the end of the day, Tjoa's work is historical romance in the most classic sense of the term. It would certainly lend itself to screen adaptation.

Anne Carlisle, Ph. D., reviewer and author of "Home Schooling: The Fire Night Ball"

Original Amazon Review

Saturday, September 22, 2012

FROM PRINT TO E-BOOK

September 22, 2012

Who would have thought it could be so difficult?

Having published the print version of The Battle of Chibi (Createspace, 2010)

I thought it would be a breeze to produce an e-book version. Well, it is harder than I thought.

I loved learning about the process of writing a

book. It had to be well-written, of

course. There ought not to be any

mistakes, grammatical, typos, or worse; I understand. There should be consistency in the format of

the pages and of the paragraphs; naturally.

Wouldn’t it be the

same for e-books? Well, not

exactly. The text for print must be the

same and consistent through-out, so the best format is Adobe Acrobat which

produces "pictures" of each page, as it were.

But in an e-book, the text has to flow and wrap around regardless of the size of the font or

of the page. Needless to say, page numbers

are worse than useless and an index that cannot refer to page numbers,

well! As for Adobe Acrobat, just forget

about it. On the other hand, it would be

nice for the reader to find roughly where he or she needs to be so it is highly

recommended that the Table of Contents has links to the different chapters and

chapter-like elements.

As it appeared from

the existence and recommendations of various style-sheets that different

electronic publishers could be very different, I thought it would be a more complete

education to try to publish the e-book on two web-sites.

The first site I

used required all the items I mentioned two paragraphs earlier. This exercise was like proof-reading except

that it included the “cues” to the publishing mechanism regarding paragraphs,

font styles, etc. There are no more than

a dozen of these things that one has to learn in addition to the items required

for a print edition. So it was

relatively simple to send this to an automated process on the publisher’s

web-site and in a day or two the process was done. A couple of problems were flagged for

correction and then we were done-done.

The other site

proceeded as smoothly except that the publisher’s web-site kept sending me what

I thought were mixed signals.

Specifically, it would tell me that the conversion was complete and I

would find upon proofing it that it was not.

So I tried again, and again.

Since each attempt took about three weeks, I decided that three times

was enough. I “simply” paid to have this

done for me. I don’t regret that

decision one bit.

Wednesday, September 19, 2012

Promoting The Battle of Chibi

Sept. 19, 2012

This is an attempt to promote The Battle of Chibi as an e-book.

It is available for FREE at Smashwords through Sept. 21. Available in all e-book formats.

I hope it will be available as a Kindle book the following week Sept. 24-28, also for free.

This is an attempt to promote The Battle of Chibi as an e-book.

It is available for FREE at Smashwords through Sept. 21. Available in all e-book formats.

I hope it will be available as a Kindle book the following week Sept. 24-28, also for free.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

It's the Law

Humanity of Justice

I have created a separate page for reviews but this book by Burke E. Strunsky is worth a Post (since I have recently discovered the difference between the two on Blogger).

The author makes a passionate plea for improvement in the American criminal justice system. He believes fervently that it works and requires only a little fine tuning. In making this case, he shows a fine eye for the details of marriages growing stale, the horror of child molestation, the paranoid public mind-set that allows for children to accuse adults of this, the fine lines that must be made and perhaps crossed in the pursuit of justice, as for example in the case of the application of the death penalty in California, or of "clergy-penitent" privilege, and the practical difference between the right to bear arms and the too easy access to a hand-gun when in a moment of "diminished capacity" or extreme rage.

The examples are told with great power of description and characterization; the case histories have provided for the often twisting and unexpected plots. But ultimately this is an attempt to explain; it is non-fiction written powerfully. Except that it does not persuade.

It is not for lack of passion. Perhaps a reader might be persuaded that the American judicial system works and needs only a few tweaks with better argument, more organized reasoning. In the end, this reviewer is not persuaded that lawyers and the legal system is about justice. The author quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes who might have the last word on this. He famously told Felix Frankfurter on his way to the Supreme Court that he/Felix would not go to uphold Justice but to uphold the Law. That is, as lawyers like to say, the gravamen of the issue. Additionally, it will not be so easy to regain the public trust in the system as the author passionately desires; it will, alas, be impossible to cure the system of its apparent indifference to human tragedy.

But it is bracing to read this book. The author is one lawyer that has not given up. Perhaps he will continue to campaign for limitations on handguns, reduction of truancy, more and better resources to be provided to Child Protective Services. Perhaps, more law-makers will read his book and be persuaded to a similar approach towards the Law.

Four stars out of five

I have created a separate page for reviews but this book by Burke E. Strunsky is worth a Post (since I have recently discovered the difference between the two on Blogger).

The author makes a passionate plea for improvement in the American criminal justice system. He believes fervently that it works and requires only a little fine tuning. In making this case, he shows a fine eye for the details of marriages growing stale, the horror of child molestation, the paranoid public mind-set that allows for children to accuse adults of this, the fine lines that must be made and perhaps crossed in the pursuit of justice, as for example in the case of the application of the death penalty in California, or of "clergy-penitent" privilege, and the practical difference between the right to bear arms and the too easy access to a hand-gun when in a moment of "diminished capacity" or extreme rage.

The examples are told with great power of description and characterization; the case histories have provided for the often twisting and unexpected plots. But ultimately this is an attempt to explain; it is non-fiction written powerfully. Except that it does not persuade.

It is not for lack of passion. Perhaps a reader might be persuaded that the American judicial system works and needs only a few tweaks with better argument, more organized reasoning. In the end, this reviewer is not persuaded that lawyers and the legal system is about justice. The author quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes who might have the last word on this. He famously told Felix Frankfurter on his way to the Supreme Court that he/Felix would not go to uphold Justice but to uphold the Law. That is, as lawyers like to say, the gravamen of the issue. Additionally, it will not be so easy to regain the public trust in the system as the author passionately desires; it will, alas, be impossible to cure the system of its apparent indifference to human tragedy.

But it is bracing to read this book. The author is one lawyer that has not given up. Perhaps he will continue to campaign for limitations on handguns, reduction of truancy, more and better resources to be provided to Child Protective Services. Perhaps, more law-makers will read his book and be persuaded to a similar approach towards the Law.

Four stars out of five

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

Reviews and Author interviews

Having blogged a few reviews, I have decided to create a new page for them and while I was at it to create a new page for author interviews. The reviews will stay for an indefinite time.

But the author interviews will be spaced out--one a week and each to stay on for four weeks. I shall also "tweet" about each interview.

If I get ambitious I shall remove the reviews that have previously appeared as blog posts and put them on the review page.

But the author interviews will be spaced out--one a week and each to stay on for four weeks. I shall also "tweet" about each interview.

If I get ambitious I shall remove the reviews that have previously appeared as blog posts and put them on the review page.

Saturday, July 21, 2012

China Boy, by Kay Haugaard

For a change of pace, this is a review of the above book.

It is a pleasant, quiet read; a fictional account of a young man who arrives in the California Gold Rush from Guangdong. The story is somewhat idealized so we are spared real nastiness although the author writes about the rise of anti-Chinese feelings that ultimately produced the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1880. To keep the score even, there are nasty moments among the Chinese themselves--greed, jealousy, tongs.

With hard work and the help of some friendly Chinese and non-Chinese, the main character thrives and finds his sister--presumed lost in some floods in Guangdong, she has actually made her own way to the Beautiful Country. The author, writing in 1971, found the sister's bound feet worthy of remark. Perhaps it is but most traditional Chinese prefer not to speak about it. The author presents a truer picture of the success of the Chinese in that period in showing how many prospered in the restaurants and laundry establishments as opposed to striking it rich in the mines. In general, it has been remarked, more money was made off the miners than in the mines; logically, this presents a puzzle for economists. The book does not go into the railroad building and other later activities and troubles of the immigrants. The plot and character development in the book do not invite comment.

Many books have been written about the coming of the Chinese to America, from Gunther Barth's pioneering (1964) Bitter Strength and T. Y. Char's edition of recollections (1975) of those who made it to The Sandalwood Mountains (Hawaii). The most detailed recent work of H. M Lai (2004) Becoming Chinese American focused on the Chinese in California arriving before the Exclusion Act and the social and other organizations they created. It is safe to say that the descendants of those who arrived in the 19th century are not conscious of being foreign in America.

It is a pleasant, quiet read; a fictional account of a young man who arrives in the California Gold Rush from Guangdong. The story is somewhat idealized so we are spared real nastiness although the author writes about the rise of anti-Chinese feelings that ultimately produced the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1880. To keep the score even, there are nasty moments among the Chinese themselves--greed, jealousy, tongs.

With hard work and the help of some friendly Chinese and non-Chinese, the main character thrives and finds his sister--presumed lost in some floods in Guangdong, she has actually made her own way to the Beautiful Country. The author, writing in 1971, found the sister's bound feet worthy of remark. Perhaps it is but most traditional Chinese prefer not to speak about it. The author presents a truer picture of the success of the Chinese in that period in showing how many prospered in the restaurants and laundry establishments as opposed to striking it rich in the mines. In general, it has been remarked, more money was made off the miners than in the mines; logically, this presents a puzzle for economists. The book does not go into the railroad building and other later activities and troubles of the immigrants. The plot and character development in the book do not invite comment.

Many books have been written about the coming of the Chinese to America, from Gunther Barth's pioneering (1964) Bitter Strength and T. Y. Char's edition of recollections (1975) of those who made it to The Sandalwood Mountains (Hawaii). The most detailed recent work of H. M Lai (2004) Becoming Chinese American focused on the Chinese in California arriving before the Exclusion Act and the social and other organizations they created. It is safe to say that the descendants of those who arrived in the 19th century are not conscious of being foreign in America.

Saturday, July 14, 2012

Spy novel: work in progress

THE NORTH KOREAN DEALER

(A suburb of Shanghai)

By sheer and meaningless coincidence, the North

Korean arms dealer Kim arrived in Shanghai the same day as the Spymaster and

his party returned to Beijing from their journey to the West. Kim arrived in a small jet as the traffic

from Pyongyang was tiny relative to that from London or almost any other part

of the world to China. His flight had

been brief and uneventful, from one tightly controlled part of the world to

another.

Kim looked forward to a week of relatively greater

freedom in Shanghai; he had a couple of friends to visit with, old school and

army chums now on various missions for their country. He intended to do a little shopping, to pick

up gifts for his mother and sisters. Of

course, he would indulge in a taste he had developed in his earlier career in

the North Korean foreign ministry serving in Eastern Europe—that for blondes of

well nourished proportions.

Passport control posed no issue for Kim as he was

scrupulous with his documents although he could also count on the alliance

between his country and the People’s Republic. This was true also of his passage through customs

control. Kim was not so foolish as to

try to smuggle anything through China; not only did he have nothing to

declare, he had nothing he had brought with him except for his briefcase. His bodyguards Ban and Kang would have all

their hardware cleared in a diplomatic pouch as pre-arranged by their Embassy.

Kim’s life in North Korea offered every comfort and

protection that the state could provide.

In China, he would enjoy the protection of the local police in addition

to that of his personal body-guards and the security detail from his

Embassy. His two body guards were from

the elite corps that protected the leadership of the state; they would each

take a twelve hour shift and the security detail consisted of three two-man

teams that would each take an eight hour shift.

Perhaps the East European flesh peddlers would have made additional

arrangements as well, for he was one of their most important—profitable--customer. Kim had heard that there were negotiations

between them and a local underworld gang and it amused him to consider the

irony of such a situation.

He walked through the busy airport oblivious to

discreet video and personal tracking of his movement through to the curb and

paid no heed to anyone who followed his car as it sped off to his safe-house. He was only mildly irritated to find that

they were stuck in a traffic jam that seemed to stretch in every direction as

far as the eye could see. It could mean

an extra hour for him to brush up on Ukrainian so he put on the earplugs of his

mp3 player. Then he paused and changed

his mind and speed-dialed a number.

“Hello,” said an accented voice, neutral in tone.

“Viktor, Kim here.

I wondered if Nadia might be available in an hour or so—we are stuck in

traffic from the Airport. … Also, I wondered if she might be available for a

week.”

There was a slight pause before Viktor

responded: “Of course, Mr. Kim. I shall call you back if there is any

problem. If not, you can expect Nadia at

your place in an hour and a half.”

Kim heaved a sigh; this was a new departure. He had known Nadia, her working name, since

he met her in Kiev more than ten years ago.

They had met from time to time until Kim returned to North Korea. A couple of years later, she showed up in

Shanghai and they had resumed their occasional dalliance. But he had usually seen her for a night or

two and there had always been others.

Now … life might be getting complicated.

Nadia had the radiant look of Renoir’s women; she

might have just stepped out of one of his paintings minus forty pounds or so

but with her bust-line intact. She was

always ready and enthusiastic without any off-putting, metallic hint of

professionalism. If she bore any scars

physical or emotional from her life, Kim had not detected them. She was comfortable with silence; she was

happy to chat, and she was not embarrassed to admit ignorance of this or

that.

She never inquired about Kim’s work even when he

spoke of his frustrations and stress and, whether he was able to spend an hour

with her or a day, she accepted the situation with equanimity and good cheer. When they first met, he was nearly thirty and

she was in her early twenties. The years

had been kind to her; she might have gained some gravitas but not an ounce of

avoirdupois.

In a following car, Agent Li, formerly the Sergeant

Major, compared his notes with those of his Shanghai police liaison, Old Gong. This police liaison had been arranged with Commissioner

Wen, the Spymaster’s friend on the Committee on Public Safety. Old Gong belonged to a national command for

counter-terrorism that did not report to regional authority, that is, the

Shanghai metropolitan police command.

Li was aware that he had much to learn about

following a suspect from his seasoned police companion and was relieved to hear

that he had committed no serious errors. The policeman on the other hand was impressed

that the intelligence agency had actually asked for his assistance. Inter-agency relations, even

inter-departmental ones within the police force, tended to be on the short side

of courteous.

As Kim arrived at his safe house, another car drove

up and Nadia stepped out with a small valise.

She smiled and slipped an arm through Kim’s and the couple entered, followed

discreetly by the bodyguards. Kim

showered as Nadia made herself comfortable, and then they embraced and slipped

into bed hungrily.

“I have missed you, Nadia.”

“It is good to see you, Kim. I am glad you are safe.”

***

At about the same time as Kim started going to

school, his father began service in the elite corps serving as bodyguards to

the Great Leader (Kim Il-Sung, no relation). By the time the

Eternal President passed away, Kim’s father was well established in the

hierarchy of the Party. His standing

helped pave the way for Kim’s progress through the Army and then in the foreign

affairs ministry. Kim was not exempt

from the political indoctrination and military training required of all, but

his father’s influence put him into the most favorable positions possible and

under the most sympathetic mentors he could have had. It also made life comfortable for his mother

and his sisters.

The posting to various embassies in East Europe

were far from luxurious. Like many other

North Koreans abroad, Kim was expected to generate revenue for the State. From generic smuggling to drug running, Kim

quickly moved to arms dealing. He had a

flair for negotiations. His very first

customer was desperately in need of ammunition of certain kinds. Kim checked with North Korean Army Logistics

and learned who were the most likely suppliers and then tracked down who were

their recent and not so recent purchasers.

He was dogged in his pursuit of details and

actually enjoyed the give and take of the bargaining process. For this customer and many others to follow,

he learned who had inventory to spare and his instincts led him surely to the

limits of each exchange. When these

transactions were successfully concluded, Kim’s earnings for the State accumulated

to a substantial amount; even more valuable was the enhancement to his

reputation for this would provide him with customer referrals and repeat

business.

The confusion in the armed forces of the states

newly independent from the Soviet Union undoubtedly furnished him with many of

his solutions. But by far the greatest

advantage Kim had was his willingness to work incredibly long hours and,

perhaps even more important, to consider the possibility that three or four

trades might be required to provide the solution for a particular

customer.

On one occasion he created a daisy chain of deals

involving six parties—a beleaguered drug cartel in South American with cash to

burn but running out of hardware, a cash-strapped African warlord, two rogue

elements in different Middle Eastern armies, a cynical sub-contractor working

for the West, and an Afghan warlord. Each

party required two weeks work each--compressed into two days for Kim. In the end, each party got what it wanted, at

a slightly higher price than it had originally been willing to pay. Kim’s legend grew wildly, but he was thoroughly

exhausted.

In the fifteenth year of his career as arms dealer,

he learned about the Pashtuns and the opportunity to earn 30 million Euros for

a product his country manufactured. This

was for him the equivalent to what had famously, fatuously, been described at a

world-historical moment as a “slam-dunk.”

***

“Nadia, would you tell me your real name?”

“Why? Nobody

uses it anymore!”

“What is it?

Surely, you don’t use Nadia for your passport.”

Nadia looked at Kim with unrehearsed questions in

her eyes. In Kim’s she saw unresolved

hope, wishful thinking, and weariness.

Kim himself was wondering what he had started.

“I tell you anyway; it is Oksana Brodsky. But you know my life--I must live one day at

a time-- it is easier to stick to Nadia.”

“Thank you Nadia--Oksana Brodsky. Perhaps you are right.” He smiled then asked: “Would you like to go shopping tomorrow?”

As Nadia beamed, he added, “I need to visit with a

couple of friends so I’ll drop you off at a nearby shopping mall and pick you

up in three or four hours. Get yourself

three or four dresses.”

“Will we eat out or …?”

“What would you prefer?”

“If you don’t mind, I’d like to get all dressed up

but eat in.”

“That’s fine with me. I’ll have Ban order for us.”

“And not Chinese food, if you can manage, please.”

“We can manage that.”

They embraced again and Kim resumed his exploration

of Nadia’s voluptuous curves, luxuriating in pneumatic bliss.

Friday, July 6, 2012

REVIEW: Lee Fullbright, The Angry Woman Suite

This novel is very well-written with a strong voice. The voice overwhelms the three points of view

from which the story is told: Elysse,

the step-daughter; Francis, the step-father, and Aidan, Francis’ school teacher

and mentor who is friend to both. Each

has a small group of significant companions—the wise and good grandfather, the

damaged aunt, the lovers, and above all Magdalene, David’s mother and the model

for the Angry Woman Suite, a set of ten paintings. These paintings were intended, we are told,

to represent a marriage, but we are also told, there is nothing loving about

them. The novel, like the paintings, is

suffused with anger, hate and pain—“the hurting is always caused by someone who

loves you and you love back.”

Of Magdelene herself, it is said that she is “suspended

between avoidance and obsession.” Like

one of the characters in an episode, the reader moves through the story as if

striding through “corridors redolent of old urine and spent dreams.” What love shows through in brief moments here

and there in the novel appears when there is comfort that comes from “recognition

of the beloved.” Withall, this is a

bleak and unsettling story; yet, it is nonetheless a compelling read.

Now we know--that the corollary of a Romantic piety is not true--that our saddest thoughts do not yield our sweetest songs. But they do yield novels that deserve to be read.

Friday, June 8, 2012

John LeCarre, An Appreciation

John LeCarre gave us an alternative to the glitzy hi-jinks of James Bond

in 1963 with The Spy Who Came in From the Cold and followed up in 1974 with

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Otherwise,

the spy novel would surely have continued in the rut of dare-devil hero versus the Bad

Guy(s) with the formulaic certainty, quite comforting after all, that good

would triumph over evil after a tour of some of the more hedonistic watering

holes of the jet set.

LeCarre’s places were almost always dingy by comparison, except perhaps

for the embassy parties in The Constant Gardener; and instead of superheroes in

five star restaurants and hotels, he took us into the world of spy craft,

deception, interrogation, and into the minds of the spies. In one Eastern

European country, “surveillance was not usually a problem, for the security

forces knew next to nothing about watching streets.” Back in London, Smiley drove past the “unlovable

fascades of the Edgeware … the sky was black with waiting rain, and all that

remained of the sun was a lingering redness on the tarmac."

With all the power in his writing and his interest in the motivation of

his characters, LeCarre reinvented the spy thriller as psychological novel. “It is a habit in all of us,” he noted, “to

make our cover stories our assumed personae, at least parallel with the

reality.” Therefore a good spymaster should

take more seriously the opposition’s cover stories. Similarly, the interrogator must beware the

almost automatic urge to project himself into the life of a man who does not speak.

When Smiley finally uncovers the mole in the Circus, “he saw with

painful clarity an ambitious man born to the big canvas… for whom the reality

was a poor island with scarcely a voice that would carry.” The mole’s initial betrayals were at first

limited to “directly advance the Russian cause over the American.” It was the realization, after Britain’s

failure to assert itself at the Suez Canal, that its situation was inane that

led him to become a mole working unreservedly for the Russians.

The literary and geopolitical landscapes have changed since he wrote. There is still the temptation to write about

covert operations as opposed to the gathering and analysis of intelligence. But writers today do not pause and savor words

as fussily as LeCarre did. There are new

enemies and battles to be fought but alas the same jingoism (to be avoided we

hope by the better writers).

Above all, in the twilight of the bipolar world (divided between East

and West, the Iron Curtain, or as it was once asserted between the inheritors of Latin Christianity and the epigones of Greek Orthodoxy) there is the challenge to write of geopolitics and intelligence in

this new world without the artistic device of a Manichaean battle between good

and evil. Would that he were still here

to show us how.

Wednesday, May 30, 2012

Women in "The Romance of the Three Kingdoms"

The proper place for women is first described in Romance in the first chapter in which

many signs appear suggesting the decay of the Han Dynasty. Cai Yong, a senior minister called upon to

explain these unusual conditions wrote a memorial to the Emperor “asserting

that the rainbow in the harem and the metamorphosis of the hens signified the

improper influence of the imperial consorts and the eunuchs in public policy.” The Emperor being indeed under the influence

of the eunuchs did not do anything; civil unrest in the form of the Huang Jin

rebellion ensued.

When the Emperor Ling lay a-dying (chapter 2 of the Romance), the succession was disputed

between his wife and his mother, that is, the Empress He who naturally

supported her own son Bian, and the Empress Dowager Dong who protected Xie, the

son born to one of Ling’s concubines.

Both had the conflicted support of the eunuchs, who were inclined in the

final analysis to support the Empress Dowager (secretly) since they had less to

fear from her. As she watched the

Empress Dowager’s political moves, the Empress He decided to confront her at a

banquet. She declared: “As women, it is not proper for us to

participate in court matters. In ancient

times, the Empress Dowager Lu, wife of the first Han emperor, attempted to

obtain power and as a result her paternal clan was totally exterminated. Now I believe, we should seclude ourselves,

‘under nine layers’ as the saying goes, and leave matters of state to the councilors

and our elders. Thus, our nation will

continue to enjoy good fortune.”

Dong overplayed her hand when she accused He of having Xie’s

mother poisoned and declared that she, Dong, could eliminate both He and her

brother He Jin, the military commander-in-chief. He protested and said: “I have tried to urge a positive approach,

why such anger on your part?” To which Dong

replied: “You are from a family of

small-time butchers, what would you know?”

Even though it portrays them as less than inspiring

figures, this episode does not demean the position of the women; it simply

shows them with motives and actions more or less comparable to that of the male

actors in the story. Indeed, He’s

reference to the consequences of the Dowager Empress Lu’s attempt to gain more

authority than was her due, makes it clear that she at least recognized what

the ground rules were – she recognized the limits of female intrigue.

The case of Lady Cai, second wife of Liu Biao, is very

similar; she wanted to increase the influence of the Cai family in Jingzhou and

relied on her brother Cai Mao. Together

they made Biao’s younger son Liu Cong over Liu Qi, the oldest son. (Whether Cong was her own son or not is

beyond the scope of this essay; my own opinion is that he was not.)

When, after the Battle of Chibi, the leaders of Jiangdong

schemed to regain Jingzhou, the role of women is shown to be more complex. Much has been made of Sun Quan’s filial piety

to his mother; in addition one should consider the mother’s actions. When she found out about the scheme to use

the offer of Quan’s sister in marriage as a ploy to lure Liu Bei to Jiangdong,

she was furious. When Quan tried to pass

the blame to Zhou Yu, Lady Wu grew even more furious: “So the great Zhou Yu, protector of six

prefectures and eighty-one cities, cannot think of a better way of getting

Jingzhou than to use my daughter as bait!

If you kill Bei, her life will be ruined; who in the world will consider

a proposal for her marriage? You all are

such geniuses!”

After the marriage of the princess (Lady Sun) to Liu Bei,

their relationship appears to be that almost of equals. Bei wanted to get back to Jingzhou but, he

told Lady Sun, he did not want to do so without her and she of her own free

will decided to leave Jiangdong with him.

When troops sent after them to prevent Bei’s escape finally caught up

with their party, she faced the men down: “Do you only obey Zhou Yu? Do you dare act against me? If Yu has the power of life and death over

you, do you think that I do not have the same power over him?”

Of course, women do not play a major role in the Romance; it

is after all about the future of “all under Heaven.” Only in the twentieth century have women

gained the right to vote. But the

Romance is supposed to be reflective of the popular culture seen through the prism of

15th century literati neo-Confucianism. The position of women in China would get

worse; it was under the Qing that various chastity laws were promulgated. (The Qing, however, also tried to put an end

to foot-binding but in this they failed although they succeeded in making men

wear the "pigtail".)

All this is to say that sweeping generalizations about

Confucius/Chinese tradition being anti-feminist are misguided.

Saturday, May 19, 2012

Fate and Loyalty in "The Romance of the Three Kingdoms"

One of the aspects of the Romance that makes it a classic

is that it is not only a collection of fascinating stories, poems, battle

scenes, political or military tricks/strategies; it is also suffused with a

moral philosophy, perhaps with more than one.

Values matter more or less to the participants in the story; they always

matter to the narrator or compiler of the Romance. Of these values/beliefs are two that collide

as the action unfolds: loyalty and fate.

Loyalty begins with filial piety on the not unreasonable

assumption that a son filial to his father and ancestors would be loyal to his

lord and to the Emperor. The first step

on the ladder of civil service would be to be recommended for one’s “abilities

and filial devotion” (舉孝廉) as

was Cao Cao when he was twenty (Romance,

ch. 1), even though he becomes the leader of the Usurpers of Han imperial

authority. Of Zhou Yu, it was said that he

“unfailingly respected his elders” (以交伯符, Romance, ch. 57).

At

the same time, the idea that Fate determined one’s life events was fairly

universal. Sun Jian, the founder of the

Wu kingdom in Jiangdong was known more for his martial prowess than the depth

of his understanding of astrology; nonetheless, in chapter 6 of the Romance, he remarks that the emperor’s

star had grown dim, foreshadowing the fall of the dynasty.

While

planning the final battles of Chibi in chapter 50 of the Romance, Liu Bei and Zhuge Liang of the Loyalist party discuss

whether or not Guan Yu could be counted on to guard the final pass that Cao Cao

would have to pass through in order to reach safety; they were both aware of

his strong sense of honor and felt that since Cao had shown Guan some kindness

in the past, Guan would find it difficult to capture Cao. Liang remarked that he had consulted the

astrological charts and found “no indication that Fate has determined Cao’s

capture”; therefore giving the assignment to Guan Yu would allow him to earn

merit with mercy and “that is also a good thing.”

Chapter

54 of the Romance provides another

striking example of the importance of divining what Fate has in store. In this chapter, Sun Quan and Zhou Yu of the

Wu kingdom that had briefly joined the Loyalists to defeat the Usurpers scheme

to use a marriage proposal to the Loyalist Liu Bei (offering Quan’s sister as a

bride) in order to lure him into Jiangdong where he can be held for ransom (for

the province of Jingzhou). Zhuge Liang

agrees with Liu Bei that this is very likely what the Wu leaders intended, but

declares that consultation with the stars indicate that nothing untoward would

happen to Bei; he therefore urges Bei to accept.

This

notion of Fate extends well beyond the Three Kingdoms: Graff, in his Medieval Chinese Warfare (Routledge, 2002), noted that there are several

chapters on divination in Tang dynasty military manuals even though the

historical records, written by more orthodox Confucian scholars, tend to

obscure the role of such practices.

Ichisada Miyazaki, 1981, China’s

Examination Hell, documents the widespread belief that Fate and spirits

influenced if not determined the results of China’s vaunted examination system.

In

the context of the events of the Three Kingdoms, when it seemed clear that the

Han dynasty was in trouble, there was bound to be a collision between the value

of loyalty and the belief that Fate determines the course of events; what

should be the proper role of a man who wished to remain loyal when it seems

clear that the dynasty is failing, i. e., losing its mandate to rule? How can loyalty be demonstrated when it would

appear that the Mandate of Heaven decreed a change?

By

the time of the Ming dynasty, the scholars had given sufficient thought to this

question and, no doubt with the encouragement of the imperial court, codified

the proper response: a man who had sworn

to uphold a dynasty could not change his allegiance even if the Mandate of

Heaven decrees otherwise. Those who had

not sworn allegiance were free to choose which side they each would

uphold. This was not so clear at the

time of the Three Kingdoms and the uncertainty is reflected in the Romance (compiled during the early Ming

dynasty). Such uncertainty gave rise to

debate and argumentation that provides an additional dimension of interest to

the stories in the Romance.

In chapter 37 of the Romance,

Liu Bei meets Cui Zhouping, a close friend of Zhuge Liang’s (the target of Bei’s

search for an advisor in his quest to restore the imperial order). Zhouping declares that order and disorder

both proceeded from Heaven, that “peace is getting old and there is cause for

dried up spears to be wielded again all over,” and that once Heaven had

determined the course of events man should not stubbornly attempt to reverse it

(命之所在,人不得而強之乎). Bei asks to hear more but declares “I am a servant

of the Han and have sworn to support it; I would not dare to leave it to Fate.” At this point, Zhouping pleads ignorance of

contemporary affairs and declines to engage in further discussion. While, Bei’s oath-brothers Guan Yu and Zhang

Fei are dismissive of the encounter, Bei seemed anxious to hear more on the

subject.

The clash of

these values/beliefs is most clearly stated in chapter 43 of the Romance in which Zhuge Liang debates the

councilors of the Wu kingdom as well as Sun Quan himself. During the debate, Liang is asked what he

thought of Cao Cao; he replies curtly that Cao is a traitor to the Han at which

point one of the Wu councilors, interjects to say that the Han era had passed

and that Heaven would dispose of its end.

Liang replies harshly that in embracing Fate, such a person has

dishonored his father and his ruler (天下之所共憤﹔公乃以天數歸之,真無父無君之人也).

Another of the Wu

councilor asserts that Cao’s legitimacy did not only spring from the fact that

he was holding the Son of Heaven hostage but also because he, Cao, was related

to a former prime minister serving the Han.

Liang replies that, in that case, Cao is not only a traitor to the

imperial dynasty but is also despicably lacking in filial piety for he is

rebelling against the ruler and the dynasty his ancestors had served (不惟漢室之亂臣,亦曹氏之賊子也).

Liang provides something of a resolution of this collision

of values in what might have been the end of his mission to forge an alliance

between Bei’s Loyalist forces and those of Wu/Jiangdong; he meets with Sun Quan

who asks the question why Bei remained defiant of Cao while a reasonable assessment

of the military situation might lead others to conclude that it would be best

to submit. Lord Bei, Liang said, remains

defiant because he does not accept that Fate should determine his actions, let

others do what they would; Bei would not yield.

It would seem clear

that Zhuge Liang has been made the mouth-piece of the Ming neo-Confucian view

regarding the balance of loyalty and fate.

But it should not be assumed that Luo Guanzhong was simply toeing the “party

line.” Of the five bosom friends that

regularly met and discussed moral and political concerns, Cui Zhouping and two

others opted for the “contemplative life” while Xu Shu was Bei’s first advisor

on strategy until a forged letter brought him to his mother who was under house

arrest in Cao’s camp. Zhuge Liang of course chose to become Bei’s

second and last advisor. Just before he

met and joined Bei, however, he and Zhouping were on one of their usual

wandering trips.

One can only wonder what they discussed during those

days. It is unlikely that the proximity

of the events within the narrative of the Romance

was a coincidence, and much more likely that Luo intentionally set the

discussion between Zhouping and Bei in such close logical and chronological

proximity to Liang’s debate in Jiangdong to highlight the uncomfortable collision

of the two values/beliefs.

Monday, May 7, 2012

Mother Xu embodies "virtu"

In the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, one of the two exemplars of xian (the neo-Confucian equivalent of Machiavelli's virtu) is a woman, Mother Xu. She was the mother of the first consiglieri to Liu Bei, the Loyalist Lord of one of the Three Kingdoms. Her son is tricked into visiting her as she was held hostage by Cao Cao, the Usurper Lord of another of the Three Kingdoms. Once there, he would not be free to serve the Loyalist cause again. His mother excoriates him thoroughly for this stupid mistake and then steps into the room next door to underline her lesson by committing suicide.

The text continues to extol her xian, quoting a poem in her honor. To reflect the changing times and tastes/styles, three translations are presented here:

( From, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms,

translated by Moss Roberts, Peking, Foreign Languages Press, 1995.)

Formidable Mother Xu

honors a thousand ancestors!

The text continues to extol her xian, quoting a poem in her honor. To reflect the changing times and tastes/styles, three translations are presented here:

Wise Mother Xun,

fair is your fame,

The storied page glows with your name,

From duty's path you never strayed,

The family's renown you made.

To train your son no pains you spared,

For your own body nothing cared.

You stand sublime, from us apart,

Through simple purity of heart.

Brave Liu Bei's virtues you extolled,

You blamed Cao Cao, the basely bold.

Of blazing fire you felt no fear,

You blenched not when the sword came near,

But dreaded lest a willful son

Should dim the fame his fathers won.

Yes, Mother Xun was of one mold

With famous heroes of old,

Who never shrank from injury,

And even were content to die.

Fair meed of praise, while still alive,

Was yours, and ever will survive.

Hail! Mother Xun, your memory,

While time rolls on, shall never.

(C. H. Brewitt-Taylor, 1935).The storied page glows with your name,

From duty's path you never strayed,

The family's renown you made.

To train your son no pains you spared,

For your own body nothing cared.

You stand sublime, from us apart,

Through simple purity of heart.

Brave Liu Bei's virtues you extolled,

You blamed Cao Cao, the basely bold.

Of blazing fire you felt no fear,

You blenched not when the sword came near,

But dreaded lest a willful son

Should dim the fame his fathers won.

Yes, Mother Xun was of one mold

With famous heroes of old,

Who never shrank from injury,

And even were content to die.

Fair meed of praise, while still alive,

Was yours, and ever will survive.

Hail! Mother Xun, your memory,

While time rolls on, shall never.

Mother Xu’s integrity

Will savor for eternity.

She kept her honor free from stain,

A credit to her family’s name.

A model lesson for her son,

No grief or hardship would she shun.

An aura like a sacred hill,

Allegiance sprung from depth of will.

For Xuande, words of approbation.

For Cao Cao, utter condemnation.

Boiling oil or scalding water,

Knife or axe could not deter her.

Then, lest Shan Fu shame his forebears,

She joins the ranks of martyred

mothers.

In life, her proper designation;

In death, her proper

destination.

Mother’s Xu’s

integrity

Will savor for

eternity.

Implacable in her

principles, she thus nurtures her family.

She instructs her

children to stay true despite hardship,

To keep their spirit

unshakeable as the hills and mountains,

With righteousness from

the bottom of their hearts.

She cherishes Liu Bei,

despises Cao Cao.

She is not intimidated

by religious trappings;

She disdains the executioner’s axe.

She disdains the executioner’s axe.

She fears only that her

offspring might disgrace their ancestors.

She would rather die

than witness such degradation--

She would rather break

her loom and endure the indignities of war!

Born to this honorable

name, she would lay down her life for it.

Formidable Mother Xu

honors a thousand ancestors!

From The Battle at Chibi, translated and retold by

Hock G. Tjoa. 2009.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Our Story

This review first appeared in Goodreads , https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/2491467631 Rao Pingru wrote this charming "graphic nov...

-

This review first appeared in Goodreads , https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/2491467631 Rao Pingru wrote this charming "graphic nov...

-

In Agamemnon Must Die , a retelling of the Oresteia by Aeschylus, I wrote a chapter about Cassandra. The most beautiful of Trojan princ...

-

This is a bold, brash, bawdy and brilliant work. Purporting to be a family chronicle that the narrator obtains from a 92 year old woman fr...